„3D printing: a threat to global trade” — analyzing the forgotten ING report

Are the claims made in the high-profile 2017 report still relevant?

For nearly a year, the AM industry has been in crisis. You could even say this is the most challenging period in its nearly 40-year history.

Companies are either going bankrupt or merging in extremely compromising ways to avoid collapse. Employees are being laid off, and research and development spending is being cut.

“Restructuring and optimization” are now the main buzzwords, effectively replacing “growth and development.”

But there are two other things that put all of this in a more complex light.

Because reports state that the situation of AM companies in China is entirely different. Investments there are in full swing, local companies are increasingly serious about global expansion, and those that have already expanded pose a significant threat to Western companies.

The second issue is the unbearable paradox described in my third law of the AM market: the market’s value is constantly growing, while the value of the companies that create this market is falling.

It’s getting harder to make sense of it all…

Should we be celebrating the success of Bambu Lab in global markets and the growing adoption of AM in more areas of life? Or should we be worried that this comes at the expense of companies like Prusa Research, UltiMaker, and other Western manufacturers?

Because this would essentially mean that the growth of one company always happens at the expense of others on the market — that these two things cannot be reconciled.

So, how is it, after all? Good or bad?

While searching for answers to these questions, I came across a report published seven years ago by ING. A report that, at the time of its release, caused quite a stir and was one of the key arguments in favor of additive manufacturing.

The report’s title was attractive to AM but ominous for the rest of the industrial production sectors: “3D printing: a threat to global trade.”

This is yet another fascinating journey through time, showing the sentiment surrounding AM just seven years ago. Overall, the report is very well-written, and the arguments presented are logical. Controversial for the rest of the industrial world, but pleasant to hear for the 3D printing industry itself.

How does this report relate to the current market situation? Is it still relevant? Is 3D printing on a path that will allow the realization of the report’s predictions, or has it already missed that chance?

Is the current crisis just a rough phase of a good plan, or has the good plan already become outdated?

I will try to answer all of this…

The ominous ING report

On September 28, 2017, ING — one of the world’s largest financial corporations — published a report focused on the 3D printing industry and its potential impact on international trade, particularly import and export.

Although the time horizon presented in the report is quite distant (2040–2060), the conclusions were very concerning for traditional manufacturing industries, especially the logistics and financial sectors.

The report analyzed the potential economic consequences of 3D printing, focusing on its impact on international trade, industry, and the future of production. The key conclusions revolved around a reduction in international trade due to local production and the automation of industrial processes.

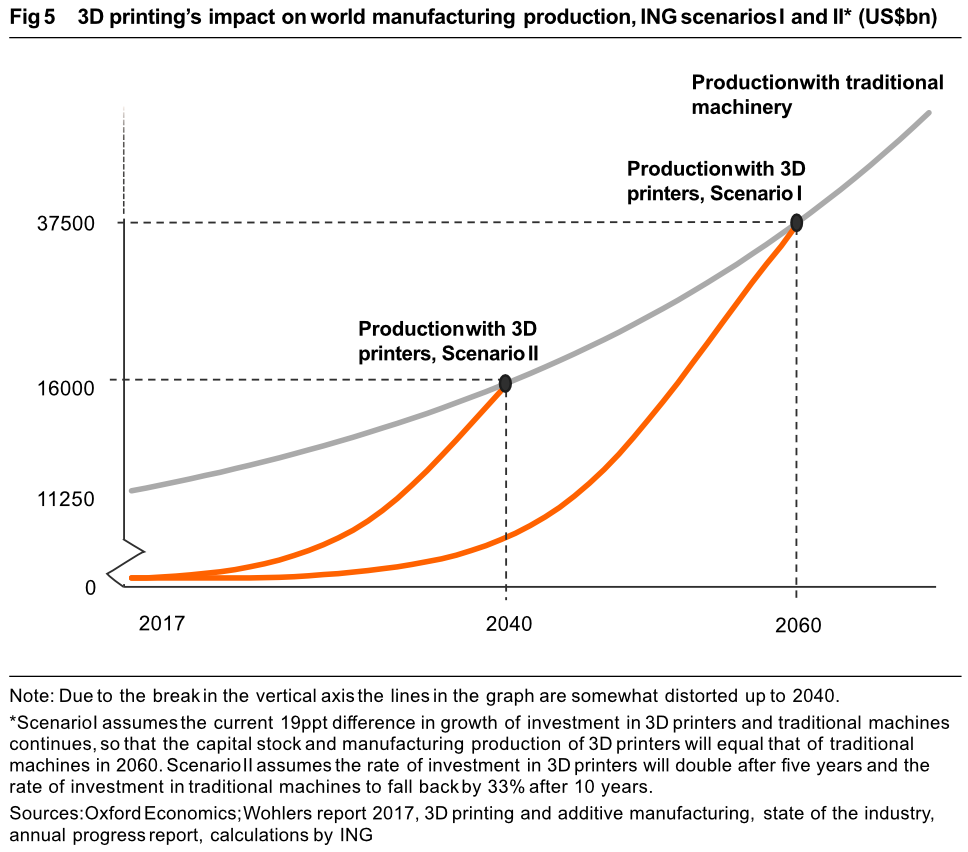

In its report, ING stated that if the current level of investment in additive technologies remains unchanged, by 2040 — or at the latest by 2060 — up to 50% of global production could be manufactured using 3D printers, depending on the scenario.

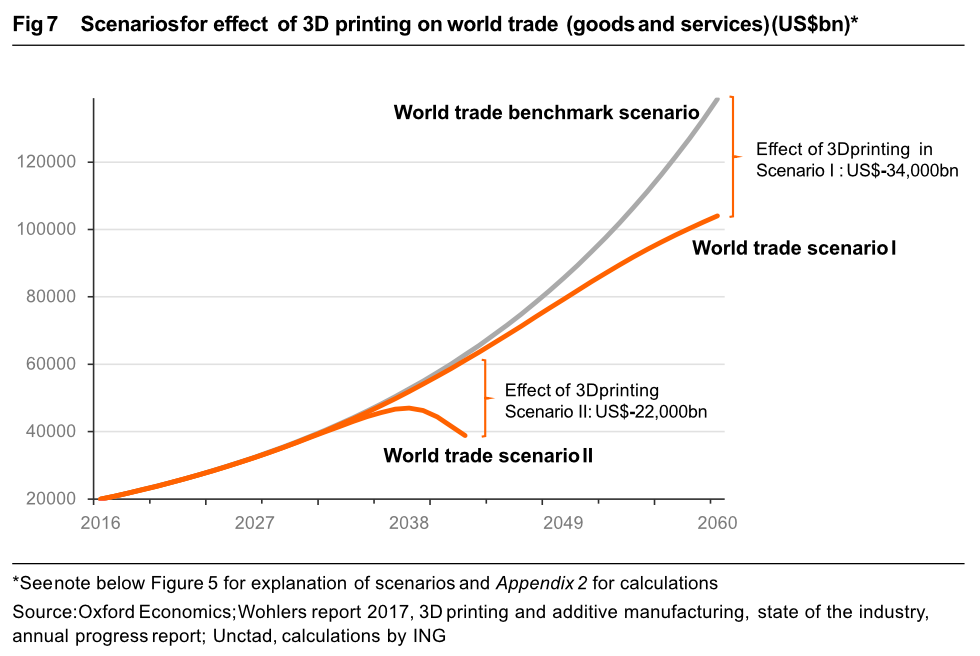

Moreover, if these predictions come true, due to the savings generated by additive technologies, by 2060, the value of global trade could decrease by about -20% by 2040 or by nearly -25% by 2060, depending on the scenario.

This would be caused by a significant reduction in the import of mass-produced goods, in favor of local, small-scale, on-demand production.

At the beginning of the report, the technology of 3D printing and its current level of development were described. According to ING analysts, in 2017, the AM sector was still in its early stages, with little impact on international trade. As the technology develops and production speeds increase, 3D printing could significantly impact global trade, especially as it becomes more economical.

The report emphasized that AM could fundamentally change the way goods are produced. 3D printing technologies require less manual labor and fewer raw materials, meaning there would be less need for importing components and finished products from countries with lower production costs.

In the long term, up to 50% of production could be carried out using 3D printers. According to the optimistic scenario, this would happen by 2040, and according to the conservative scenario, by 2060.

Another conclusion from the report is the prediction of a decline in international trade due to the widespread use of 3D printing. Local 3D printing of products will reduce the need for imports, especially from developing countries, which are the main exporters of cheap industrial goods.

As a result, global trade could decrease by 18–22% by 2060, or by 38% by 2040 in the accelerated technology development scenario.

The report identifies sectors that will benefit the most from the adoption of 3D printing. These include:

Automotive industry: Printing car parts could reduce exports from Mexico, Japan, Germany, and Canada to the U.S., as local production would replace imported components.

Industrial machinery: Many industrial manufacturers have invested in 3D printing, allowing them to produce more complex components, shorten production times, and reduce material and transportation costs.

Consumer products: Smaller and more complex products, such as consumer electronics, could be printed locally, further reducing international trade.

For the U.S., the report predicts a positive impact of 3D printing on the trade balance, especially in sectors where the U.S. has a deficit, such as the automotive and consumer products industries. Thanks to local production, imports to the U.S. will decrease, benefiting local companies.

Of course, despite the great potential, 3D printing still has limitations, particularly in terms of mass production. Most 3D printers in 2017 were used for prototyping, not for mass production.

The technology was still too expensive, and the quality of some printed products was lower than those produced traditionally. Key challenges include increasing printing speed and reducing material costs.

In the final conclusions, ING analysts state that 3D printing technology is promising, but it still has a long way to go before being widely adopted in mass production.

However, they expect that as technology advances, 3D printing will gradually change global trade flows, particularly in labor-intensive sectors and precision industries.

The report can still be downloaded from this place: 3D printing: a threat to global trade | reports | ING Think.

Has the ING report aged?

In the 2017 report, it was posited that 3D printing had the potential to revolutionize manufacturing and significantly reduce international trade through localized production.

Today, after seven years, we can say that while these claims are still relevant, the reality has not entirely matched the report’s optimistic forecasts. Let’s take a closer look at the key aspects…

Technological advancements in AM

In 2024, 3D printing technology has certainly made enormous progress compared to 2017. 3D printers are now able to print faster, cheaper, and at much larger sizes. Metal 3D printing, which in 2017 was still a technological challenge, became more accessible after 2020 and is widely used in the aerospace, medical, and automotive industries.

Major advancements have been made by Germany’s Nikon SLM Solutions and China’s Farsoon, BLT, and Eplus3D, which are competing to develop and produce multi-laser, large-format PBF systems. Whereas in 2017, parts measuring 40 cm in the axes were considered large, today, the machines from these manufacturers can exceed 1 meter in the axes.

In the area of powdered polymers, HP’s Multi Jet Fusion method has sparked a revolution, introducing AM from polyamides, polypropylene, and TPU into the world of series production.

In the field of photopolymers, Carbon, which is developing its ultra-fast AM technology, is pushing the boundaries of what can be efficiently produced on 3D printers in collaboration with leading footwear brands. The 3D printing method using LCD screens has also significantly reduced the cost of 3D printers, making them as widespread as FFF technology.

Companies like Merit3D are using resin-based photopolymer AM to break new records in the number of parts produced (exceeding millions of units) and increasingly comparing themselves to injection molding.

And finally, Bambu Lab, which has simplified and significantly accelerated 3D printing in the FFF technology, not only making other desktop 3D printer manufacturers feel threatened but also prompting Stratasys to launch the latest patent war.

However, although 3D printing technology is advancing rapidly, the predictions that 50% of products will be printed by 2040 still seem exaggerated.

Mass production of most goods on an industrial scale is still conducted using traditional manufacturing methods. 3D printing is commonly used for prototyping, small-scale production, and highly customized products such as prosthetics, implants, and parts for vintage cars, but it is not yet able to completely replace injection molding.

Automation and reduction of labor demand

The report predicted that 3D printing would reduce the demand for cheap labor imports from developing countries, as production would take place locally with fewer workers. In 2024, we see that this process is indeed happening, but not to the extent suggested by the report.

Many companies are relocating production back to developed countries thanks to automation, but not necessarily through 3D printing. Automation based on robotics and artificial intelligence has a greater impact on production relocation than 3D printing itself.

For example, 3D printers in car factories are replacing some component manufacturing processes, but this does not mean that they have completely eliminated traditional production lines.

Personalization of production

The report’s thesis about the rise of so-called “prosumerism” (the phenomenon where consumers become both producers and consumers) has not fully materialized.

While 3D printing technology for home use is becoming more affordable, we do not see a mass adoption of 3D printers by ordinary consumers. Many people still prefer to buy ready-made products rather than produce them themselves.

In the meantime, 3D printing is finding greater application in the B2B sector, particularly in the production of spare parts, specialized tools, and prototypes. Even in 2024, 3D printing for the mass consumer remains more of a curiosity than a widespread practice.

Reduction of international trade

The report predicted a significant reduction in international trade due to local production using 3D printing. In 2024, we have not yet seen macroeconomic changes on a scale that aligns with the report’s forecasts. While the technology has the potential to reshape global supply chains, international trade continues to grow, and globalization has not been replaced by the “localization” of production to the extent predicted.

Notably, some countries, such as China, still dominate mass production, and the cost of production in low-wage countries remains attractive to global companies.

Moreover, other Asian countries, previously seen as “poor and underdeveloped,” are now joining China in this dominance. A prime example is Vietnam, which is starting to play an increasingly significant role in global supply chains.

Are we following the plan?

The 2017 report presented two scenarios for the development of 3D printing: a conservative scenario, assuming that 50% of global production would come from 3D printers by 2060, and an optimistic scenario, in which this threshold would be reached by 2040.

Based on the current data from 2024, it seems we are closer to realizing the first, more conservative scenario. Here’s why…

In 2024, 3D printing is widely used in some sectors, such as aerospace, medicine, and automotive, but it remains a niche technology in many other industries.

Compared to traditional manufacturing techniques, 3D printing is more expensive and slower for mass production. Therefore, we still observe that 3D printing is more popular in custom or low-volume production rather than in the mass production of consumer goods.

One of the biggest challenges limiting the growth of 3D printing is the cost of materials. While the printers themselves are becoming more affordable, the prices of specialized 3D printing materials remain high.

In sectors like medicine and aerospace, where precision and unique materials are crucial, 3D printing performs exceptionally well. However, in industries requiring the production of inexpensive, high-volume goods, such as textiles or electronics, 3D printing is not yet a viable alternative to traditional manufacturing methods.

The report predicted that 3D printing would become competitive in mass production, but in 2024, this goal has not yet been widely achieved. While there are exceptions, most companies still rely on traditional machinery, as 3D printers are too slow or too costly for large-scale production.

The report indicated that global investments in 3D printing would grow faster than in traditional machinery. Indeed, over the past few years, we have seen intense growth in interest in 3D printing. According to industry reports, the 3D printing market grew from $6.6 billion in 2016 to approximately $16 billion in 2024.

However, when compared to the global market for traditional machinery, which is still 1000 times larger, 3D printing remains a small part of the global manufacturing market.

The report predicted that 3D printing would lead to the so-called “re-bundling” of production, meaning relocating production closer to consumers, which would reduce global trade in intermediate goods and finished products.

While in 2024 we see some signs of this shift — for example, greater use of 3D printers for on-site production of spare parts — there has not yet been a significant change in global supply chains. Countries like China still dominate mass production, and many companies continue to use traditional global production models.

Conclusion

In 2024, the world is not following the report’s optimistic scenario. Although 3D printing technology is advancing rapidly, its adoption rate in mass production is slower than expected. We are, however, on a path more reminiscent of the conservative scenario, where achieving a 50% share of global production through 3D printing might only happen around 2060.