The false start revolution

The forgotten story of Desktop Factory — the startup that was supposed to be the biggest star of 3D printing

Avi Reichental, one of the leading figures in the additive manufacturing industry, might have had a shopping addiction during his tenure as CEO of 3D Systems.

The number of acquisitions made under his leadership at 3D Systems was truly staggering. Between 2001 and 2015, the company acquired as many as 54 companies (with Reichental responsible for the transactions from 2003 onwards).

For many years, 3D Systems was the only company in the world that offered 3D printing machines in all the major additive manufacturing technologies.

Although the company initially specialized in SLA (Stereolithography), it gradually expanded its portfolio through numerous acquisitions.

Some of the most important acquisitions were:

the acquisition of DTM Corp., the creator of SLS technology, in April 2001

the acquisition of Z Corporation, the creator of Binder Jetting/CJP technology, in January 2012

the acquisition of Phenix Systems, a French manufacturer of metal 3D printers, in June 2013.

The company also acquired many smaller startups, some of which turned out to be failures:

in 2010, Bits from Bytes — one of the first two companies producing amateur 3D printers using FDM technology; it served as the basis for creating the Cube and Cubify brands

in 2013, The Sugar Lab, the creator of 3D sugar printing technology

in 2014, the infamous botObjects, which claimed to have created a full-color FDM 3D printer.

3D Systems also became a major player in the 3D software market for reverse engineering. Over the years, it acquired key companies producing such software: Geomagic, Alibre, RapidForm, Simbionix, and Viztu Technologies.

However, I would like to return to a completely forgotten story that was supposed to be a major event in the world of 3D printing but ended in total failure.

And where 3D Systems, under Avi Reichental, played a significant role at the very end. A role that didn’t change much but closed the story in an interesting way.

Here is the story of Desktop Factory — the 3D printer that was supposed to be bigger than MakerBot (before MakerBot was even born).

Desktop Factory — a revolution that never came

Desktop Factory was founded in 2004, the same year that Adrian Bowyer, a senior lecturer at the University of Bath in the UK, began work on the self-replicating 3D printer project — RepRap.

Desktop Factory had similar goals to Bowyer’s, aiming to popularize 3D printing among as many people as possible. However, instead of offering it for free under an open-source license, the company intended to sell its devices at a very low price for those times.

That price was $5,000.

Although today this seems absurd, at the time it was a truly revolutionary price. Existing 3D printers cost at least ten times more.

Desktop Factory planned to create parts from plastic. Unfortunately, in 2008, the FDM technology patent by Stratasys was still in effect, forcing the startup to seek out its own manufacturing method.

So they developed an interesting and intriguing solution:

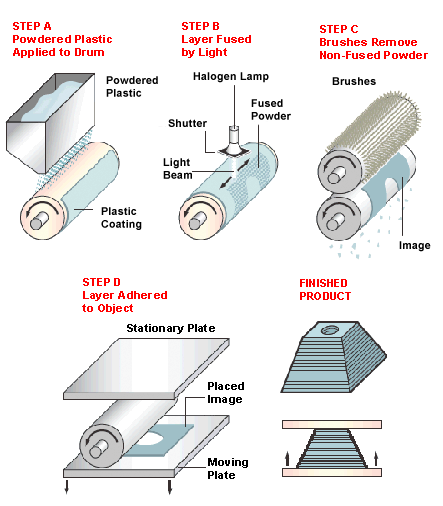

The 3D printing process was supposed to involve applying powdered thermoplastic onto a roller, where it would be selectively melted using a halogen lamp.

Then, the remaining unmelted material was to be removed, and the fused layer would be placed on the 3D printer’s build platform.

Today, it’s hard to find more details about this method, especially since Desktop Factory representatives were very reserved about it in interviews.

In one of the archival video materials I managed to find, the results of the 3D printer’s work were still far from perfect… The video is from the fall of November 2008:

But mainstream media didn’t focus on such nuances. Company representatives painted extraordinary and revolutionary visions of the future, which technology portals eagerly spread around the world.

The marketing blurb really sums up the amazing difference this will make to our lives: Imagine your child being able to select a toy from a catalog or even design his or her own and create it right at home.

(…)

Similar in size to a laserjet printer at 25 x 20 x 20 inches (and a back breaking 90lbs), the Desktop Factory builds parts in layers, using a plastic powder heated by a halogen lamp. Running costs are claimed to be as little as $0.50 per cubic inch. Not bad. The printer reads STL (Standard Tessellation Language) files, which are like the JPEG of 3D printing, and most other standard formats.

WIRED (May 09, 2007)

or

Tinkerers, schemers, makers and DIY-buffs: grab your ball-peen hammer and heaviest piggy bank, because you’re about to need a loan. A company called Desktop Factory is going to make your 3D-printing dreams a serious reality with the introduction of its 125ci 3D printer, a $4,995 hunk of concept-plastic magic which could possibly represent a paradigmatic shift for the state of three-dimensional printing for the masses.

The DF crew calls the pricing “disruptively lower than the nearest competitive offering,” and we’re inclined to agree, as most 3D printers crest easily over the $10,000 mark. The printer takes up a paltry 25 x 20 x 20-inch space, and weighs about 90-pounds, while the maximum size of printed objects is 5 x 5 x 5-inches, and Desktop Factory says per-cubic-inch printing costs will hover somewhere around $1.

One of these beautiful babies could be all yours, just put down your $495 reserve fee, and then go to work on that string of robberies you’ve been planning.

ENGADGET (September 14, 2007)

Nevertheless, the revolution still didn’t arrive.

While the RepRap project was steadily spreading worldwide, Desktop Factory remained stagnant.

In a December 2008 press release, the team reported that they were still struggling with several technological problems, the biggest of which were the halogen lamp’s lifespan and the method of cleaning the roller where the material layer was deposited from the remains of unmelted powder.

However, they still planned to bring their machine to market in the following year, 2009. But that never happened…

The fall. The reprise. The oblivion.

What ultimately ended Desktop Factory’s journey was a lack of funds…

The startup managed to secure $2 million from an investment fund, but to start production of the 3D printers, they needed an additional $1 million.

At the same time, the VC that offered the $2 million stated that they would not release the funds until all required financing was secured. Thus, Desktop Factory was without cash…

In March 2009, it was the end. Operational activities were gradually shut down, and by the summer of that year, Desktop Factory was up for sale.

And then, unexpectedly, 3D Systems expressed interest in buying the company!

Reichental’s company acquired the unfulfilled startup in September 2009.

Of course, they maintained the intention to bring the innovative 3D printer to market:

We are very pleased to add Desktop Factory’s technology to our growing portfolio of affordable 3-D Printing engines,

said Avi Reichental, president and CEO of 3D Systems.

Until recently, cost and complexity have confined 3-D Printers to the shops and design departments of major corporations and premier design firms.

The growing success and acceptance of the V-Flash System, our first sub-$10,000 compact desktop 3-D Printer, reaffirms our commitment to making 3-D Printing as common in offices, factories, schools and homes as 2-D printers are today.

We believe the technology already developed by Desktop Factory, in combination with our extensive technology portfolio, could lead to a new generation of fast, simple and affordable 3-D Printers capable of making durable plastic parts,

But in the end, it never came to fruition.

The project was shut down, and the domain desktopfactory.com redirected to the 3D Systems homepage (which it no longer does today).

The acquisition of Desktop Factory was one of many ill-considered purchases made by 3D Systems.

(But it wasn’t the worst — my personal favorite in that regard is botObjects, to which I plan to dedicate a separate article someday.)

In hindsight, it seems that the sole purpose of these kinds of acquisitions was to inflate 3D Systems’ stock price. Technologically and business-wise, it didn’t make much sense.

As for Desktop Factory itself, it’s now just a deep part of additive manufacturing history. It’s a shame that more materials showcasing the 3D printer’s operations haven’t survived, as the technology seemed at least intriguing.