The Smart Extruder of utter failure

The embarrasing story of the end of "the old MakerBot"

Today marks the ninth anniversary of the launch of the Smart Extruder+, a device intended to restore market confidence in MakerBot and lift it off its knees. The original Smart Extruder, after all, was a disaster—one of the biggest letdowns in the history of 3D printing. Although it’s hard to believe now, the list of casualties caused by this tiny device is long.

It ended the career of Bre Pettis, once hailed as the “Steve Jobs of 3D printing.” It ended the career of Jenny Lawton, who had worked alongside him since 2011 to build the "corporate MakerBot." It led to the layoffs of numerous employees and the outsourcing of MakerBot’s 3D printer production to China. It caused MakerBot’s retail stores to shut down. It brought a lawsuit against Stratasys, MakerBot’s then-owner. And finally, it resulted in a historically massive quarterly loss of -$938 million for Stratasys, ultimately leading to the departure of the company’s CEO, David Reis.

Phew... Quite the list. Oh, wait! Smart Extruder-equipped printers appeared also in the final scenes of the famous Print the Legend documentary on Netflix!

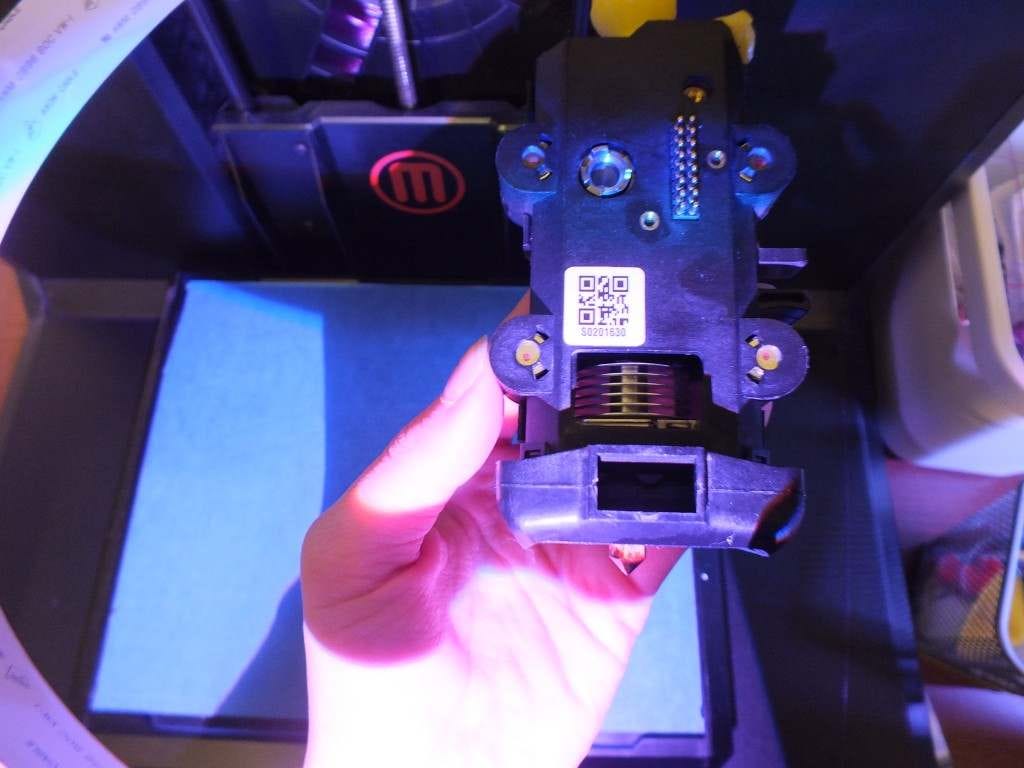

Alright, but how is that even possible? An extruder is nothing more than a component in an FFF 3D printer responsible for feeding filament into the print head. Structurally, it’s a simple mechanism: a gear presses the filament against a metal wheel, which is turned by a stepper motor. It performs just two tasks—pushing the filament down (for printing) or pulling it back up (for retraction during idle movements).

What could possibly make it “smart”? And how could it fail so badly that it led to such enormous financial, market, reputational, and personal losses?

We will start our story at the end. Since July 2015, when Stratasys shareholders filed a lawsuit against MakerBot’s parent company. Then we’ll go back to 2014 and the launch of the original Smart Extruder, and finally to 2009 and a certain document that sheds an entirely different light on this tale…

The Lawsuit

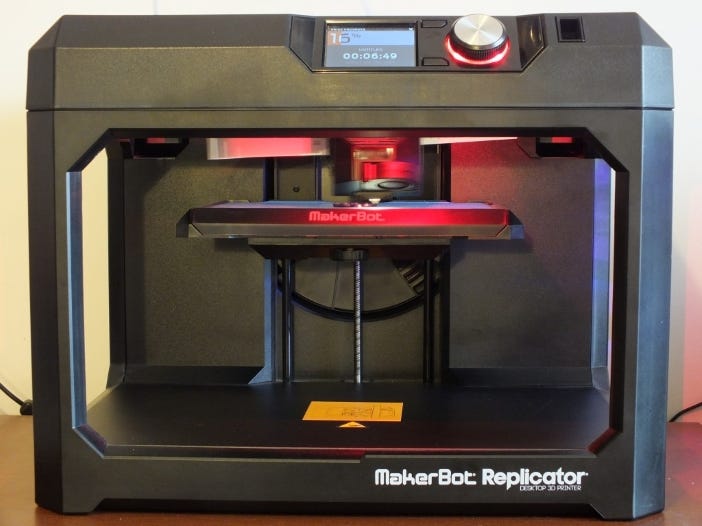

On July 1, 2015, a class-action lawsuit was filed in the District Court of Minnesota against MakerBot and its parent company, Stratasys. The lawsuit alleged deliberate concealment of design flaws in the company’s latest devices from the Replicator series—5th Gen, Mini, and Z18—specifically in the Smart Extruder. MakerBot had touted the extruder as setting a new standard for desktop-grade 3D printers using FDM technology.

Unfortunately, shortly after the market release of the 3D printers equipped with the Smart Extruder—which occurred in the first half of 2014—it became apparent that it was an exceptionally defective product, in extreme cases making the 3D printers unusable.

The plaintiffs accused MakerBot and Stratasys of hiding knowledge about the poor quality of the extruders while driving 3D printer sales and leveraging this to persuade investors to purchase Stratasys shares. When issues with the extruders eventually began to impact sales performance, the company's stock value plummeted, causing significant financial losses for shareholders.

The 125-page lawsuit remains publicly accessible at this link.

Ultimately, a year later, in July 2016, the case was dismissed. However, the verdict did not resolve whether representatives of MakerBot and Stratasys had intentionally brought a defective product to market; it only rejected accusations that they had concealed information about the flaws and/or deliberately misled investors.

Additionally, the court found that nearly all statements about the quality of the 5th Generation 3D printers were promotional in nature. Thus, while it acknowledged that MakerBot and Stratasys may have been misleading in their advertising, the court determined that this did not constitute harm to stock market investors—largely because the allegations were somewhat vague and did not fully meet the requirements of the PSLRA (Private Securities Litigation Reform Act).

An intriguing aspect of the case was the revelation of claims made by former company employees, who alleged that management was aware of the 3D printer issues but released them to the market anyway. However, the court was unable to determine conclusively whether the employees providing testimony had firsthand involvement in the events or were merely relying on "general knowledge," "secondhand opinions," or "assumptions."

At least in this lawsuit, MakerBot and Stratasys emerged unscathed. Financially, however, it remained a disaster.

On November 4, 2015, Stratasys announced its third-quarter financial results for 2015, revealing a staggering loss of -$938 million—an unprecedented figure in the additive manufacturing industry.

This colossal financial loss was primarily attributed to goodwill impairments from the prior acquisition of MakerBot (compounded by disappointing performance in Stratasys’ core business segments).

CES 2014

Let’s now return to the moment of the Smart Extruder’s debut.

Between 2010 and 2013, MakerBot emerged as the undisputed leader in the desktop-grade 3D printer industry worldwide. This success culminated in the company’s acquisition in May 2013 by one of the two largest players in the market, Stratasys.

The timing was good for MakerBot, as competitors were beginning to close. By joining Stratasys, MakerBot gained access to major retail distribution networks in the U.S. and actively expanded its sales channels globally.

However, the core challenge remained the product itself. In January 2014, MakerBot, alongside 3D Systems, wowed the world with the introduction of three new 3D printer models: the MakerBot Replicator 5th Generation, the Replicator Mini, and the large-format Replicator Z18, featuring a substantial build volume of 30.5 x 30.5 x 45.7 cm.

These new devices set a high bar with features such as a comprehensive cloud-based ecosystem, mobile device integration, and the innovative Smart Extruder—a system designed to level the print bed automatically and pause printing in case of material delivery issues.

Ironically, the Smart Extruder became the source of MakerBot’s greatest challenges and controversies. The problem? The Smart Extruder simply didn’t work as promised. It jammed, clogged, and malfunctioned—essentially, instead of simplifying 3D printing, it often made it impossible.

Moreover, the extruder wore out quickly, resulting in a progressive decline in the quality of printed models.

When the first 3D printer units reached customers, they were met with widespread disappointment. Online forums were soon flooded with negative reviews, exacerbated by the MakerBot forum administrators' attempts to delete critical comments. Users frequently cited recurring issues with the Smart Extruder, which rendered the Replicator 5 essentially unusable. Despite its theoretical potential, the printer failed to deliver in basic, critical functions.

MakerBot’s initial solution to the problem was... to monetize it!

The company offered a pack of three Smart Extruders for $495 (a $10 discount per unit) and provided a $50 discount for returning a used extruder.

Simultaneously, MakerBot worked intensively to improve the extruders’ quality. Ultimately, the issues with jamming and filament blockage were resolved in the third version of the extruder, which was released in the fall of 2014.

Around the same time, Bre Pettis, MakerBot’s founder and CEO, stepped down from his position. He was "promoted" to a role within Stratasys, where he was assigned to a small 3D printing lab called Bold Machines, focused on creating innovative applications for 3D printing.

Pettis officially parted ways with MakerBot and Stratasys in June 2015.

His position was taken over by Jenny Lawton, his long-time right-hand person at MakerBot. However, her tenure was short-lived—lasting only a few months. In February 2015, Stratasys appointed seasoned manager Jonathan Jaglom as MakerBot’s new CEO. Jaglom began his tenure by implementing significant restructuring, laying off 100 employees and closing all three MakerBot retail stores.

Before Jaglom’s arrival, Pettis, Lawton, and Stratasys CEO David Ries consistently downplayed the Smart Extruder’s problems in communications with investors. They instead engaged in a sort of “success propaganda,” celebrating rising 3D printer sales and forecasting aggressive growth for the company.

This approach directly contributed to the aforementioned lawsuit.

So what really happened?

Fearing growing competition, and stressed by Stratasys pressure, MakerBot released a product in 2014 that was not ready for consumers. Over the following months, the company worked to improve and upgrade the product, but at the expense of unsuspecting users who were unaware of the Smart Extruder’s inherent problems.

Simultaneously, Stratasys used the rising sales of the flawed product to inflate its stock value. When the truth eventually surfaced, Stratasys admitted that its earlier growth forecasts were unrealistic. Unfortunately, this revelation caused the company’s stock to plummet, leading to significant financial losses for shareholders.

Clear? In theory, yes—but there’s a deeper layer to this story...

The Manifesto

MakerBot was founded in 2009 as a tiny startup by three friends—Bre Pettis, Adam Mayer, and Zach Smith. Before long, Mayer and Smith faded from the picture, leaving Pettis in full control of the rapidly growing company. As MakerBot gained increasing market traction and secured funding for further development through early rounds of investment from angel investors and venture capital funds, Pettis brought in talented and experienced managers, including the aforementioned Jenny Lawton.

Then came the deal with Stratasys, which further accelerated the company's trajectory. But eventually... it became clear that if things continued in this direction, MakerBot was headed for disaster.

Rapid and dynamic growth cannot continue indefinitely.

When a company expands at such a breakneck pace, many issues are overlooked along the way. Problems are downplayed, and painful compromises are made to meet impossibly tight deadlines.

What once worked well in a startup environment became the primary cause of failure in a corporate setting.

At the heart of all the trouble was the Smart Extruder. How could it have been released to customers in such a flawed state? In my view, the answer lies in Bre Pettis’s famous manifesto, from March 3, 2009, which outlined the principles that formed the foundation of MakerBot's initial success.

The Cult of Done Manifesto

There are three states of being. Not knowing, action and completion.

Accept that everything is a draft. It helps to get it done.

There is no editing stage.

Pretending you know what you’re doing is almost the same as knowing what you are doing, so just accept that you know what you’re doing even if you don’t and do it.

Banish procrastination. If you wait more than a week to get an idea done, abandon it.

The point of being done is not to finish but to get other things done.

Once you’re done you can throw it away.

Laugh at perfection. It’s boring and keeps you from being done.

People without dirty hands are wrong. Doing something makes you right.

Failure counts as done. So do mistakes.

Destruction is a variant of done.

If you have an idea and publish it on the internet, that counts as a ghost of done.

Done is the engine of more.

by Bre Pettis

source: Medium.com

According to Pettis, the manifesto was created in just 20 minutes, with help from Kio Stark. It encapsulates the essence of the maker and hacker movement, perfectly aligning with the operational ethos of most startups.

When it comes to the issues with the Smart Extruder described above, the manifesto sheds light on the root of the problem. The extruder was flawed because that was the organizational culture and policy at MakerBot.

"Everything is a draft," "laugh at perfection," "stop procrastinating," and "accept that you know what you're doing, even if you don't." Given this mindset, things couldn't have turned out any differently.

Now, let’s put ourselves in Stratasys's shoes... In May 2013, it acquires a fast-growing company that is not only a leader in the low-cost 3D printing market but also poses a real competitive threat within a few years.

MakerBot is deeply engaged in the development of three new products featuring an advanced extruder, innovative for the low-cost 3D printer industry. Both companies set an ambitious deadline (January 2014 for the official unveiling at CES in Las Vegas, with a market launch at the start of Q2) and work towards it.

When they meet the deadline, it turns out that one of the key functionalities doesn’t work. Why? Because "everything is a draft," and the creators "laugh at perfection."

Of course, there’s another theory—Stratasys pushed MakerBot to rush the launch of the new 3D printers and the flawed Smart Extruder. It was the corporate machinery that caused the downfall of MakerBot's reputation and its iconic founder.

Anyway, Bre Pettis has long since left the 3D printing industry. People who entered the field during the COVID-19 pandemic—to print face shields and accessories for healthcare workers—have no idea who he was.

For them, it was Josef Průša who invented 3D printing.

No one summed up this story better than the Master of One-Liner Conclusions, the Great Jan Homola:

This is the story of how a single component can bury an entire brand and cause billions of dollars of damage... I still hate it.