Why is 3D printing no longer called 3D printing?

What is the difference between "3D printing" and "Additive Manufacturing"?

At the turn of November and December 2023, Joris Peels and Alex Huckstepp caused quite a stir with their critical articles about the condition of the 3D printing industry. Peels — long associated with one of the world’s largest 3D printing portals — 3DPrint.com , tried to be somewhat restrained in his assessments, but Huckstepp laid it all out on the table, uncompromisingly dealing with all the pathologies and myths shrouding the industry in a fluffy blanket of false comfort.

The articles sparked a major discussion, and most commentators confirmed the theses of both authors.

However, there were also voices sugarcoating the current situation. In an article published on December 12, 2023, in 3DPrint.com titled “RIP 3D Printing. Long Live AM!”, its authors John E. Barnes and Timothy Simpson defend the 3D printing industry, claiming among other things that one should not confuse concepts and not equate “3D printing” with “additive manufacturing” as they are two completely different issues.

That 3D printing is a small and consequently disappointing thing, while AM is the future and a kind of “Champions League” of the industry.

I have a slightly different view on this issue. It doesn’t matter what we call it — at the end of the day, we’re still talking about the same thing.

However, what is interesting is where the need to change the prevailing name came from? How is „AM” better than „3D printing”?

In the world of ecology, we deal with the concept of “greenwashing” — a form of advertising in ecology which is deceptively used to persuade the public that a company or a product are environmentally friendly, although in reality they are far from it.

In the world of 3D printing, we are dealing with something similar, but in a completely different context. I call it “forced industrialization”.

Where did the name “3D printing” even come from?

At the beginning, there was “stereolithography” and “stereolithographic apparatuses”. Then came “Fused Deposition Modelling” and “3D Modeller”, followed by others — “Selective Laser Sintering”, “Laminated Object Modeling”, and “Solid Ground Curing”.

Until in 1993, scientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) developed a method of creating three dimensional models from gypsum powder, selectively bonded with sprayed adhesive. The technology used was known from inkjet printers, which in this solution applied adhesive to gypsum powder instead of ink to paper.

This technique was named “3 Dimensional Printing techniques” — in short, “3D printing”. And although no one realized it at the time, it was this shortened name that became the foundation of the dynamic growth in popularity of additive technologies worldwide.

3D printing sounded “cool” and captured people’s imaginations. No Avarege Joe would ever buy a stereolithographic apparatus — a 3D printer is something completely different…

The first additive machines were intended for a very narrow audience — engineers and designers from large manufacturing companies and research staff from universities or scientific institutes. They were used for rapid prototyping — in the 90s and 00s, no one thought about trying to use them for the production of end-use parts (unless in the category of experiment).

The machines cost a lot of money and worked “so-so” — in terms of the quality of 3D prints and handling, they were far from what we are accustomed to today. Sales were minimal, and awareness that such machines even existed was even smaller.

This changed with four people: Adrian Bowyer, Bre Pettis, Josef Průša , and Avi Reichental.

How did 3D printing become „the next big thing”?

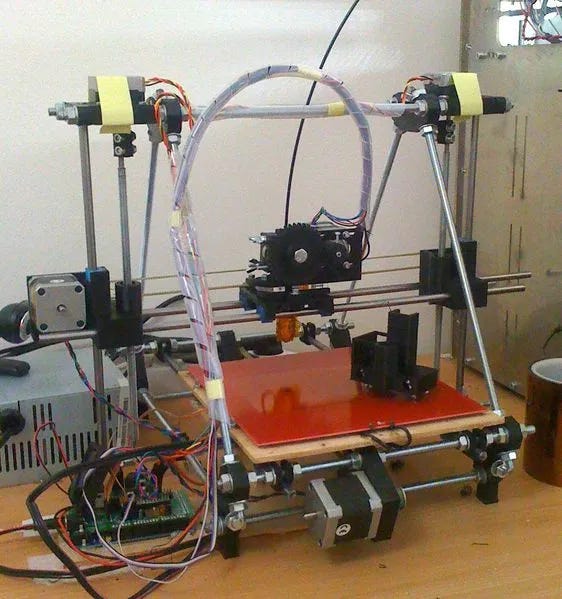

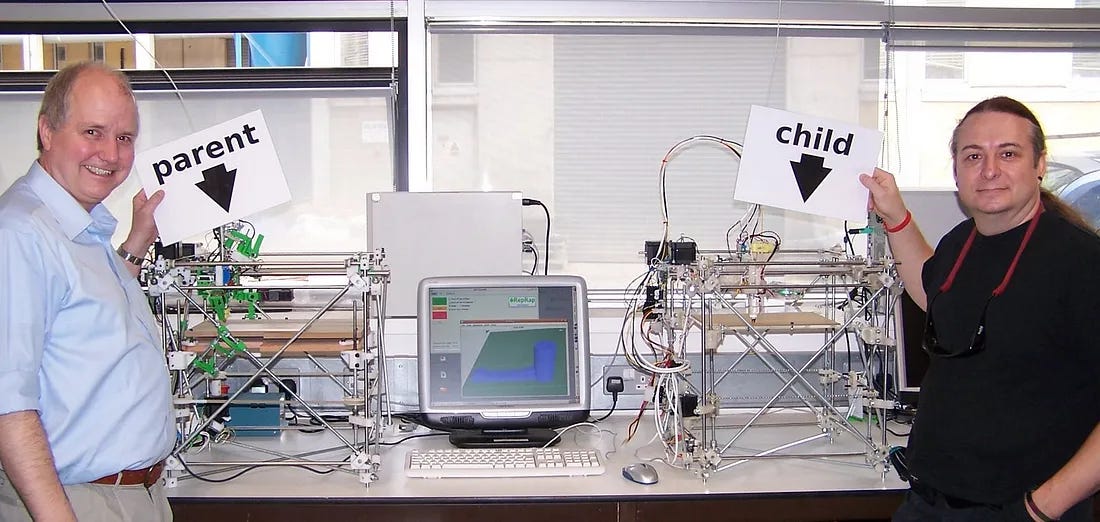

Dr. Adrian Bowyer — a senior lecturer at the University of Bath in the UK, developed in February 2004 the concept of creating a so-called “self-replicating 3D printer” — in short, “RepRap”.

It was based on constructing a device using on one hand generally available construction materials, and on the other hand elements created using additive technologies, which could later be replicated for the needs of its copies.

The project was intended to be open-source and possible to be created by anyone who has basic competencies, knowledge, and skills in mechanics and electronics. The most important aspect of the entire project was to be the price of the device — several hundred to several thousand times lower than the prices of commercial devices of this type available at the time.

As for the technology it was to use for printing, FDM — a method developed by Stratasys was chosen. Given that the name Fused Deposition Modeling was a proprietary name of the company, Bowyer invented its alternative description — Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF). The pioneering 3D printer was named Darwin.

Thanks to the publication of the RepRap project online, it gradually gained popularity. By September 2008, there were already over 100 self-built Darwins operating worldwide. On November 30 of the same year, Wade Bortz became the first person outside the University of Bath to print parts for another RepRap on a 3D printer he built himself. The revolution began to spread wider and wider…

The birth of MakerBot and low-cost 3D printing

In 2007, the RepRap project caught the attention of an American teacher — Bre Pettis, who first encountered it in Vienna, during his travels around Europe. Two years later, in 2009, his colleague — Zach Smith suggested he and Adam Mayer open a start-up involved in the production of the first, low-budget 3D printers.

The company took the name MakerBot Industries, becoming the first company in the world to produce and offer proprietary 3D printers derived from the RepRap project. In the early period of its operation, Adrian Bowyer himself invested $25,000 in it.

The debut device was Cupcake CNC — a 3D printer based on a box-like wooden structure. It was first presented in April 2009. It had a working area of 10 x 10 x 13 cm and was sold as a kit for self-assembly.

In September 2010, during Maker Faire in New York, MakerBot presented the second model of its 3D printer — Thing-O-Matic. The device had a slightly smaller working area (10 cm in each axis), but was equipped with a heated, aluminum table, new, improved control electronics, and communication via USB or SD card.

In August 2011, the investment fund The Foundry Group invested $10 million in MakerBot, and its representatives joined the company’s board. By that time, MakerBot had sold about 3,500 of its devices.

Josef Průša and the open-hardware revolution

While MakerBot Industries was taking its first steps in business, the topic of low-budget 3D printers caught the interest of a young Czech, who quite accidentally pushed the RepRap project in a completely new direction…

In 2010, Josef Průša — a DJ with a big technological bent, in search of tools and manufacturing methods that would allow him to independently create controllers for the console from which he played music in clubs, stumbled upon the RepRap project.

He decided to build his own 3D printer, but quickly found that the Mendel project was too complicated and simplified it.

He published the simplified version online and to his surprise, it quickly became the most popular and most frequently built version of a 3D printer. The project was dubbed “Prusa simplified Mendel”, starting an entire series of devices.

Soon, its next iterations appeared — Prusa i2 and Prusa i3 — the most popular and most frequently copied design in the world. Although Průša always emphasized the randomness of the enormous popularity of his projects, there is no denying that thanks to their simplicity and the quality of their construction solutions, the popularity of RepRaps dynamically increased.

When 3D printers got covered in glitter and entered the disco

So, we have a man who invented an inexpensive 3D printer, which — THEORETICALLY — anyone can build themselves, a man who decided to create the first business around it, and a man who simplified the initial, “free” project and helped significantly propagate it around the world.

But it still lacked the right flair…

In April 2009, RapMan — a 3D printer for self-assembly by Bits From Bytes — the second company after MakerBot Industries to produce cheap 3D printers, debuted in the UK.

Seeing the big potential in the newly emerging business — Avi Reichental, then CEO of 3D Systems, decided to have a part in it and in October 2010 his company acquired Bits From Bytes. The British company’s team was involved in producing the first series of low-budget 3D printers Cubify (Cube and CubeX).

And then it really all started…

Reichental and the charismatic Pettis became pioneers of the fashion for “3D printers”, which were soon “to stand in every home”, and each of us was to independently “print anything we desire”.

“Everyone’s a maker” — was one of the main slogans of the new revolution. They were followed by a whole host of imitators — Ultimaker, Robo 3D, Printrbot, Solidoodle, LulzBot, Zortrax, Formlabs, and hundreds of others, scattered all over the world.

This process had two climaxes: the first on June 20, 2013, when MakerBot was acquired by Stratasys and the second in January 2014 at the CES in Las Vegas, where MakerBot / Stratasys and 3D Systems presented a whole host of exciting new products that were to take the industry into the stratosphere.

Today, we know that, excluding the MakerBot Z18, each of these devices turned out to be a huge flop, causing more harm than good to each company. But at that time, the speculative bubble was still growing, the stock prices of 3D printing companies were soaring, and the technology itself was seen as one of the greatest inventions of humanity.

In 2015, it all suddenly ended… The bubble burst, Bre Pettis disappeared from the 3D printing firmament forever, Avi Reichental re-emerged only a few years later with NEXA 3D, and a whole host of companies that grew during this crazy run collapsed (except for the thriving Formlabs and Ultimaker, and the struggling Zortrax and LulzBot).

A charming story, but what about “3D printing”?

It’s hard to say when the phrase ‘3D printing’ became dominant in people’s consciousness, but one thing is certain beyond any doubt: if 3D printers continued to be called stereolithographic apparatuses, 3D Modellers, or similar, nobody would have taken them seriously.

It was 3D printing that opened people’s eyes to this technology, because it made it easier for them to understand. A 3D printer is a printer that, instead of texts and images on paper, prints real objects. Brilliant, right?

Unfortunately, after 2015, this term was trivialized by mainstream media and lost its attractiveness in the eyes of potential investors. 3D printer manufacturers were associated with MakerBot suing users of malfunctioning SmartExtruders, non-existent 3D printers for chocolate and sugar, and cash-draining, unprofitable FDM/FFF printers that were unclear in their purpose — certainly not for home use as commonly portrayed.

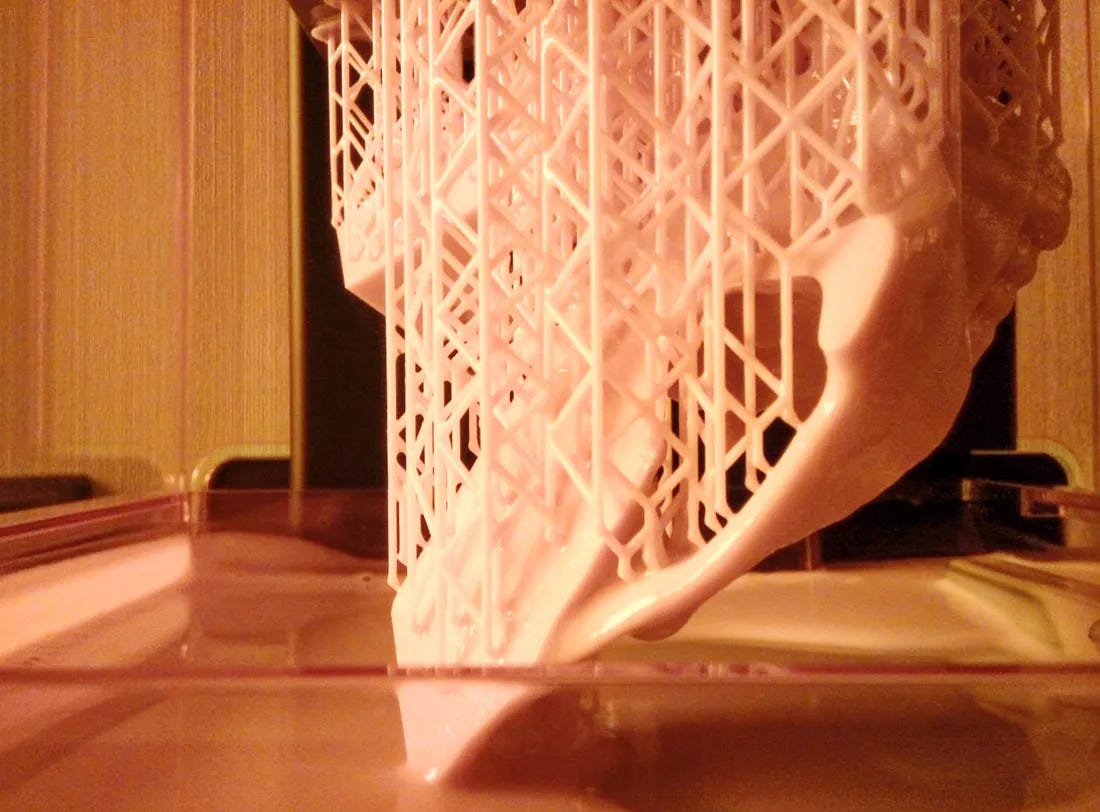

Besides, 3D printers were small, colorful, prone to failure, and completely unsuitable for industrial users. They 3D printed with PLA, ABS, or PETG (which was still very niche at the time) and were completely unsuitable for working with serious industrial-grade materials like polyamides, polycarbonates, or PEEK.

At investor meetings, it was hard to defend the concept of industrial SLS or SLM 3D printers when everyone still had the image of will.i.am and his ‘signature’ EKOCYCLE — a modified version of Cube 3, printing with ‘eco-friendly’ filament made from recycled plastic beverage bottles.

Therefore, once again, some very smart people came up with the idea to simply change its name. Replace ‘plastic, amateurish 3D printing’ with industrial, professional ‘Additive Manufacturing’.

The Birth of AM — from now on all 3D printers are industrial

After 2016, it was clear to any reasonably intelligent person that the consumer market in the context of 3D printing was dead. Those who could not reconcile themselves to this fact turned to education, but this market was never as big and simple as the consumer market seemed. From the beginning, the natural environment for 3D printers was the industrial segment, and this is the direction the entire industry took.

From then on, all 3D printers — regardless of the technology used, were industrial. They no longer produced ‘everything you desire’ — they made ‘parts’.

They stopped being used for prototype production — they started being used for the production of end-use parts and small production batches.

Of course, technological progress played a big part in this — the 3D printers of the first and second halves of the 2010s are worlds apart, and the developments post the C19 pandemic further highlighted this progress.

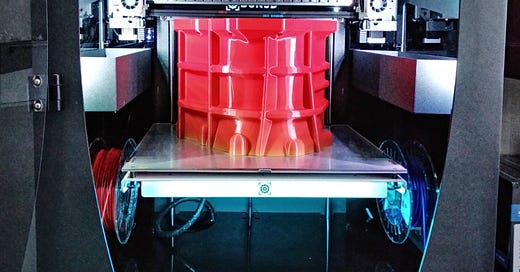

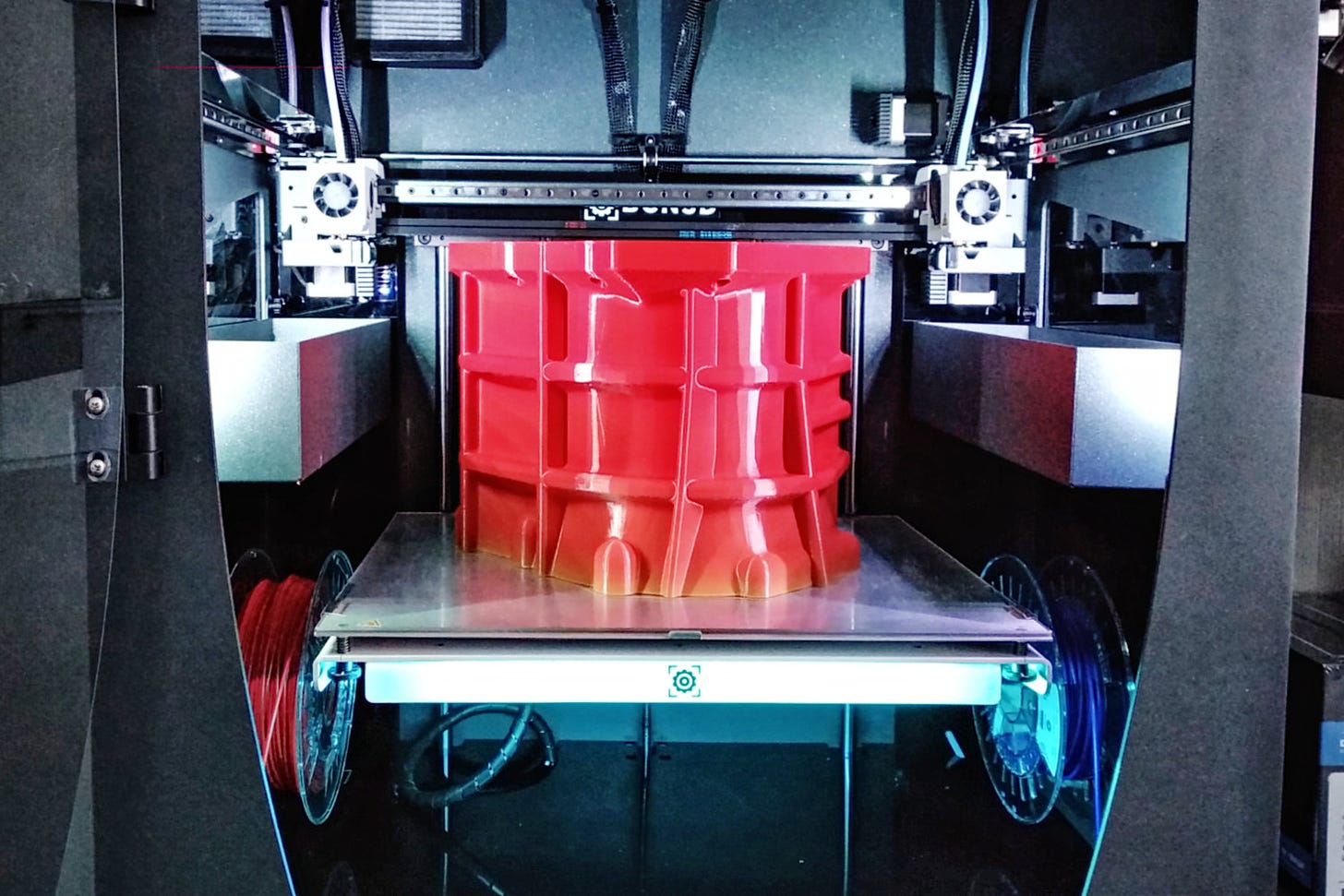

Desktop 3D printer manufacturers changed their tack and started industrializing them. They increased build volumes, added enclosed heating chambers, better print heads, filament flow sensors, better construction components.

In short, they started making the same 3D printers as before, but ‘on steroids’. They still used stepper motors, relied on the same free software and firmware.

Meanwhile, new players from the outset abandoned the thought of delving into the ‘discredited’ FDM/FFF. Since photopolymer 3D printers were ‘taken over’ by the Chinese, they focused on higher technologies — 3D printing with metal and powdered polymers. Thus, a new generation of startups was born, growing as quickly as MakerBot once did.

However, the purpose of these changes was never application-based, but always business-based. Companies started manufacturing industrial 3D printers solely because the consumer ones had failed. There was a ‘forced industrialization’ — in short, ‘Additive Manufacturing’.

At the end of the day, 3D printing and additive manufacturing are the same manufacturing method. The same as in the 80s and 90s of the last century — only more modern and repeatable. We can call it whatever we like…

This article was originally published on LinkedIn on December 25, 2023. This is a reworked version.